I have been in Columbia, PA for the last few days. After arriving a day early to do some clock and watch related sight seeing including a visit to Merritt’s Clocks and the NAWCC Museum, class time arrived.

I have been in Columbia, PA for the last few days. After arriving a day early to do some clock and watch related sight seeing including a visit to Merritt’s Clocks and the NAWCC Museum, class time arrived.

I have been doing clock repair for a while now and feel like I can generally take care of most things wrong with a clock. I have been hoping to get to that level of skill on the watch side as well, as my collecting habit exceeds my financial ability to pay for someone else to service my watches. I received an email announcement about the NAWCC’s Introduction to Pocket Watch Repair class and decided it would be a great opportunity to take some of the fear out of tearing into a watch.

The Introduction to Pocket Watch Repair class is a two-day class that covers removing a watch from its case, disassembling and cleaning it, and then reassembling the watch. Implicit in this I suppose is that the watch is supposed to work when I’m done with it.

I have been pursuing clock repair for several years now and feel reasonably comfortable tearing into time only and time and strike movements. The advantage of these clocks is they’re relatively simple one and two-train clocks, and the parts are largely big enough to see (though pivot polishing benefits from magnification), and large enough to repair or re-fabricate if necessary. Watches on the other hand – even relatively large pocket watches are a different story. Much of the work needs to be done under magnification and parts replacement in the modern era is largely done by scavenging from parts movements sourced on Ebay or antique stores due to the difficulty of creating replacements.

I was under no illusion that a two-day introductory class would make me a watchmaker, but I hoped that a guided walkthrough would be a good first step for someone like me who has some desire to be able to do this but will never have the time to go to watchmaking school.

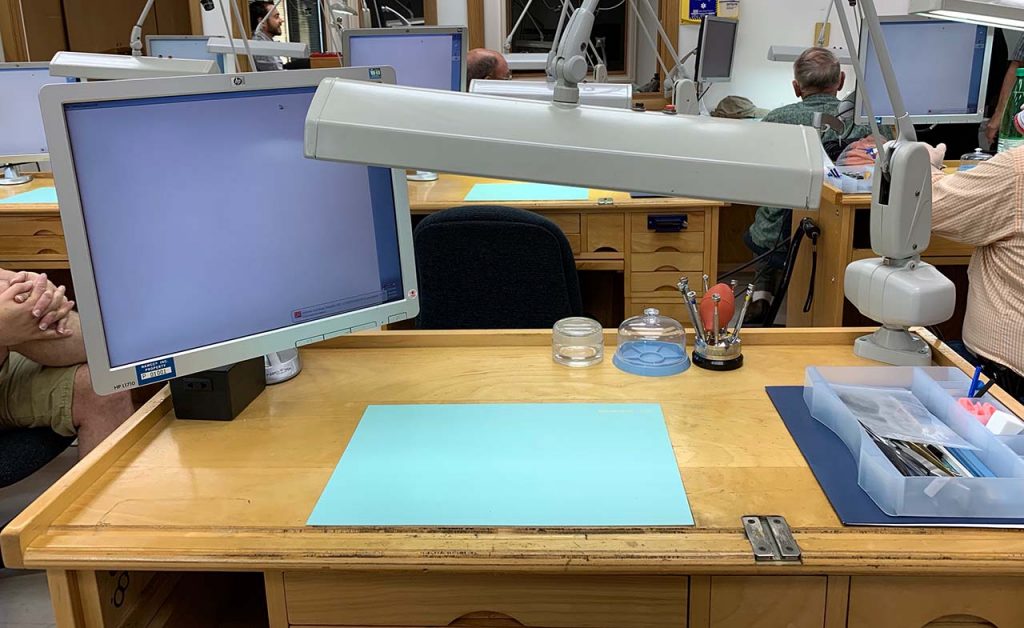

This class covered disassembly, cleaning, and oiling and reassembling an Elgin 12-size watch. All materials were provided – I just showed up and sat down.

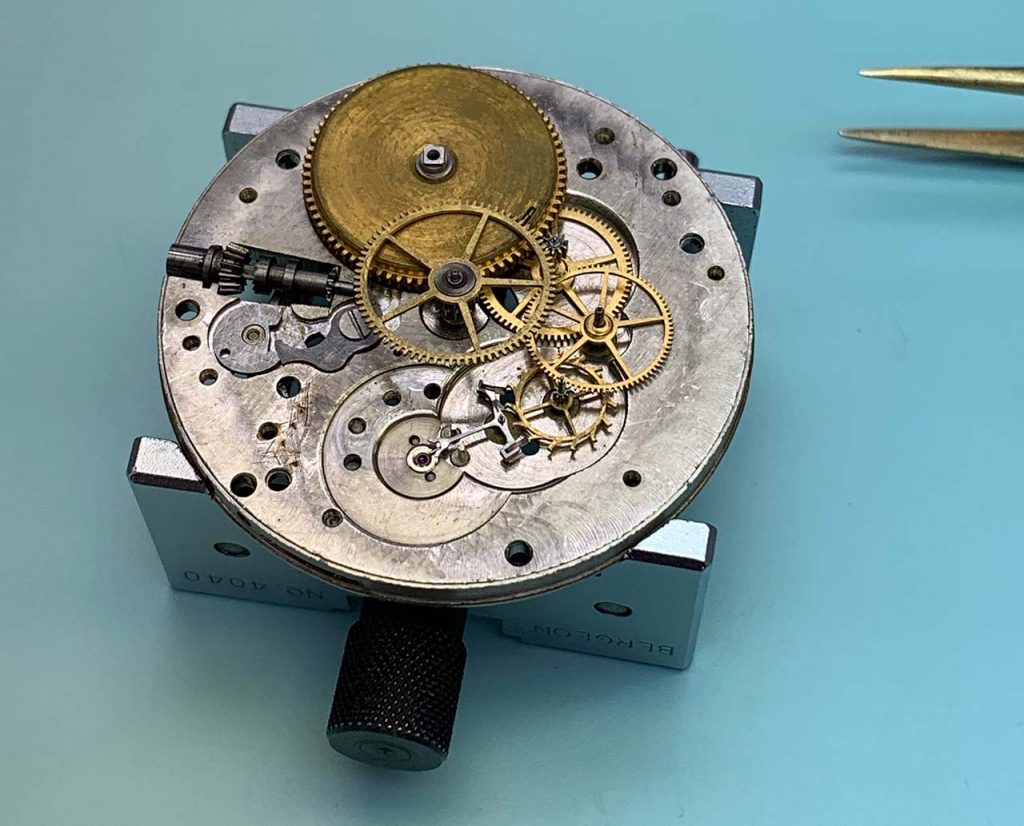

My victim, er, repair subject was this Elgin 12-size watch.

Elgin 12-size watches were chosen because they are extremely plentiful and inexpensive, and so that everyone in the class would be working on the same movement.

The first day of the class consisted of learning how to use a loupe, tweezers, and screwdrivers, and basic disassembly and reassembly of the watch.

Around lunchtime we had been guided through full disassembly of our watch.

The afternoon of the first day covered partial reassembly, again just to get us time on the tools.

I have an Optivisor at home which magnifies for both eyes, however we used a single eye loupe. This took some adjustment – at first closing the other eye, but then learning to keep it open and let it go unfocused. In the end, I grew to understand why watchmakers work this way – the focal distance of your loupe eye is 2 to 3 inches, and the screw you need to pick up is 8 inches away. With only one loupe, you have a close-focusing eye and a normal-focusing eye. The hardest thing for me to adjust to was trying to gauge depth perception with just one eye. I found myself not knowing where my tweezers were relative to what I was trying to move with them. Our instructor told us that adjustment isn’t too difficult and our brain uses cues like shadows to know where things are.

The balance assembly is the most delicate part of the watch, containing the hairspring, the balance, and the balance cock. The balance rotates around the balance staff, the pivots of which are microscopically small and very fragile. Normal disassembly of a watch requires removing the balance assembly, and while doing that, the balance hangs precariously from the stretched-out hairspring.

This picture shows the winding and setting mechanism on the left side, and the gear train. The pallet fork is silver at the bottom of this picture, and has two jewel stones which contact the escape wheel.

The second day of class included disassembling the watch again and cleaning the components in a solvent with a small brush.

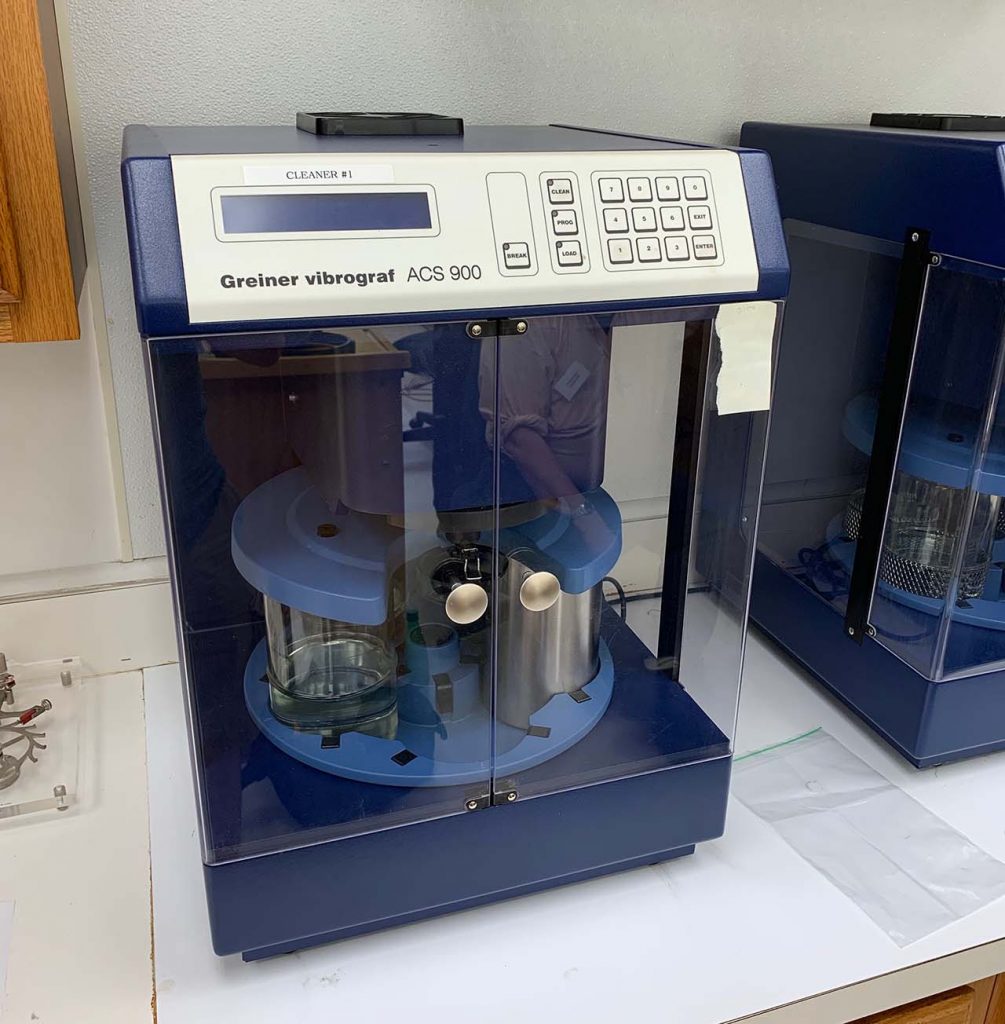

The classroom was equipped with a pair of cleaning machines each costing as much as a very nice used car, but thankfully we learned a method that, though it wouldn’t impress a real watchmaker, is reproducible at home.

After cleaning the parts, we re-oiled the appropriate locations and began reassembly. The most difficult part is aligning the pivots into the bridges. A fellow classmate attempted to pound the bridge back on, resulting in our instructor crying “That’s not how you put a watch together!” Thankfully I didn’t have too much trouble. I think many hours of pivot alignment on a larger scale with my clock repair work gave me a sense of the mechanics and I was able to translate it to the watch.

In the end after losing one screw and dislodging one of my pallet stones by being overly aggressive in cleaning the pallet fork, my watch ran approximately as well as it did before I started “fixing” it, which I consider a personal success.

I thought the class was well worth the time and the trip. I’m sorry that I am unavailable for the second part of the class later this year. Hopefully I can catch other classes in the future as time allows.