The Minnesota Clocks & Watches household is coming up on the end of the second week of semi-quarantine, just in time for Governor Walz’s “shelter in place” order to extend it another couple weeks. We are adequately stocked with toilet paper and have enough carbs in the cupboard to feed a small marathon. I bought Super Smash Brothers to play on our Nintendo with our boys and there’s been a lot of floor hockey happening in our bonus room. Thus far we haven’t killed each other. I don’t mean to overly make light of a very serious situation, but a little levity is necessary for surviving the isolation.

The Minnesota Clocks & Watches household is coming up on the end of the second week of semi-quarantine, just in time for Governor Walz’s “shelter in place” order to extend it another couple weeks. We are adequately stocked with toilet paper and have enough carbs in the cupboard to feed a small marathon. I bought Super Smash Brothers to play on our Nintendo with our boys and there’s been a lot of floor hockey happening in our bonus room. Thus far we haven’t killed each other. I don’t mean to overly make light of a very serious situation, but a little levity is necessary for surviving the isolation.

Our children seem to absorb a lot of the extra time we’re supposed to have (no commute, no social events) but I have managed to get in a little repair work in. I’m continuing to work on the batch of clocks I purchased from an estate last month. I just finished up this Colonial grandfather clock. Colonial made so many models it’s hard to pin down exactly when this was made, but I’m guessing 1920’s – 1930’s.

The clock stands about 75 inches tall. It counts the hour and strikes the half hour on a nice mellow sounding coil gong. The case is a vey dark brown. In low light it’s almost black. The metal dial is bronze colored. I’m not quite sure it’s fair to call this Mid-Century Modern, but it’s heading in that direction.

Colonial Manufacturing was based in Zeeland, Michigan and operated from 1906 – 1987. They were a prolific maker, and in the 1970’s had nearly a third of the market share of large clocks in the US. Colonial was primarily a casemaker, using movements manufactured in Germany.

This clock’s movement is stamped Colonial Mfg Co, Zeeland Mich, Germany. The movement manufacturer is stamped Haller & Benzing Schwenningen A.N.

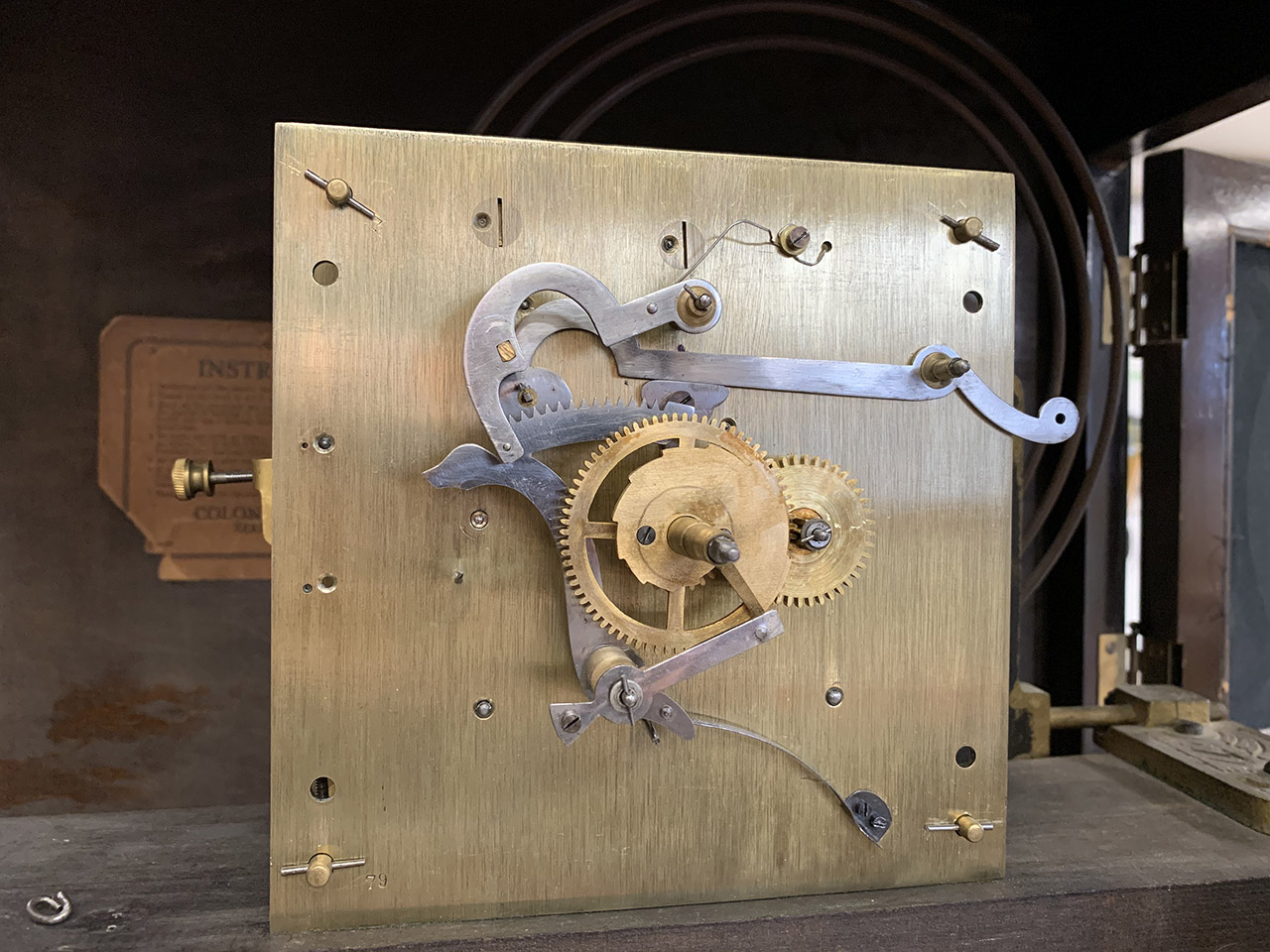

The movement was a dream to work on. It has nice thick plates, and all of the strike synchronization is done on the front side of the movement, which saves considerable hassle in trying to hold all of the levers and pins in place while putting the movement plates back together. With this style of movement, the trains can be assembled between the plates without any care in alignment, and the levers can be adjusted later. This is in contrast to count wheel-style movements where assembly is an iterative exercise in frustration and cursing, trying to coax all of the pivots into their holes while holding the gear train to mesh in just a certain way.

This clock is a bit newer than most I work on, and that plus good design and probably some reasonable care meant that the overhaul wasn’t as daunting as a lot of what I get. A full disassembly and ultrasonic cleaning followed by polishing the pivots to a mirror finish and a bit of polishing and cleanup work to rest of the movement was the extent of what it needed, and back together it went. Note the adjustable pivot holes – the circles near the top of the plate with a slot to rotate to adjust alignment. No bushings were required.

The most challenging part of the whole repair process was dealing with the weight chains. The chains have a large ring on the free end and a link with wide arms that stick out on the weight end. The holes in the seatboard (the wooden board the movement sits on) are very small to ensure that careless winding won’t pull the chains all the way through the clock. To remove the clock, the chain must be split to remove one or the other of the large links that interfere with the seatboard holes. For disassembly, it’s advantageous to split the chain on the weight end as you can then pull the chain all the way through and out of the movement. For reassembly the reverse is better – removing the ring on the free end allows a string to be fished through the movement and the case to fish the chain through without fighting the ratcheting mechanism.

I did a bit of case work to repair some torn fabric on one of the access doors where someone had punched through.

This was a very satisfying project. Some of the clocks I see are incredibly worn and it becomes a calculation problem of how much work they are worth, considering the low prices of clocks at the moment. This clock, on the other hand, needed a 30,000 mile tuneup, rather than a 200,000 mile drivetrain replacement. I am confident the clock will run very well for a long time. This clock needs is a new home. Maybe yours?

I have begun work on two more from the batch – an American tall case from about 1850 and an English brass dial clock from about 1725. More on these soon!