Much of this site is dedicated to very old things, but I think what lies at the root of my love for horology is the intersection between art, story, and technology. I love the craftsmanship of old pieces – especially handmade things. I love to consider the generations that enjoyed the clock or watch before me. More than those things, though, I appreciate the technical ingenuity of clocks, and in many cases timepieces have been at the forefront of technological innovation for nearly 400 years.

From the invention of the pendulum clock by Huygens in 1656, mechanical clocks have marched steadily onward: enhancements in materials, escapement design, power regulation, and construction methods. For the first 300 years those advancements were in materials and mechanisms. That changed with the quartz crystal, beginning in the 1930s for scientific instruments, and making its way to ubiquity in the 1970’s.

The quartz movement was almost the death of the mechanical watch and clock industry. The advantages of better timekeeping, the lack of daily winding, better ruggedness, and in many cases lower prices were irresistible to many. In the ’80’s and ’90’s massive consolidation in the industry happened resulting in movement development moving to a new organization called ETA, and many of the storied brands moving to case design and marketing.

Tissot is one of those brands – a business formed in 1853 in Switzerland that ended up as part of the Swatch Group. The Swatch Group has brands that run the price gamut, from the plastic Swatch brand at the low end to Breguet and Omega at the high end. Tissot is priced somewhere in the upper middle. I have owned a number of Tissot watches. I find the quality to be significantly higher than the mall fashion brands like Rado and Skagen but lacking the marketing silliness of some of the high-end brands.

Tissot has a wide product portfolio, including modern pocket watches – something that few other companies still make. About half of the watch models are quartz and half are mechanical, with the mechanical watches using movements from fellow Swatch Group company ETA.

The Dive Watch

Dive watches are attractive and recognizable. Sean Connery’s and Roger Moore’s James Bonds wore Rolex dive watches in several Bond films, and Pierce Brosnan’s Bond later wore an Omega Seamaster. They are sporty without being dizzying, and they offer a balance of toughness and functionality with the rotating bezel offering a good-enough version of a chronograph for most tasks.

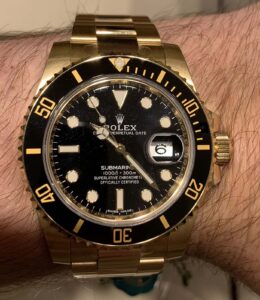

The quintessential dive watch is probably the Rolex Submariner. It’s a gorgeous piece and I would gladly wear one if someone gave one to me. Unfortunately the $8500 price tag (the 14K Rolex Sub pictured on my arm while visiting a dealer is more like $24,000; $8500 gets you the Stainless Steel version after an 18 month or so wait) reflects a good chunk of marketing couture in addition to the admittedly nice watch. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, that goes a long way to explaining the inflated price of the Rolex, as the style of the Submariner is one of the most copied watches ever.

Tissot Seastar 1000

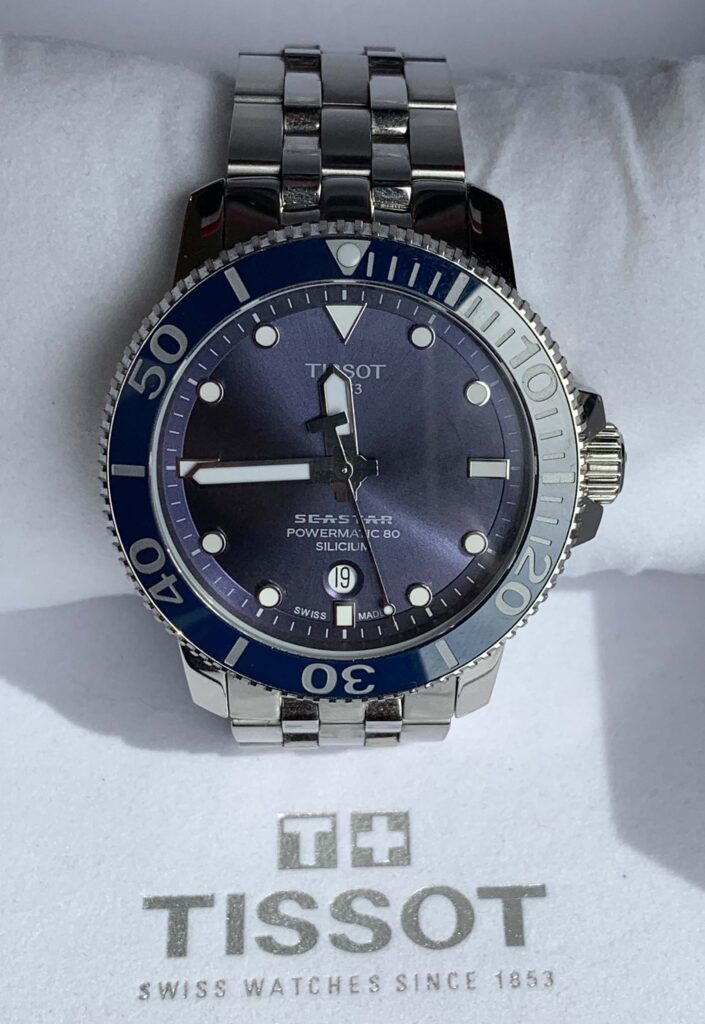

Tissot’s version of the dive watch is the Seastar 1000 series. It is available in both quartz and mechanical, and also a quartz chronograph. There is a forthcoming limited edition mechanical chronograph as well based on the ETA 7750 movement, but as far as I can tell, no general release of that watch.

The Seastars have stainless steel cases with a variety of watch straps and colors. The crystal is sapphire and the watch has a display back. The watch is adjusted via the screw down crown, and the ceramic dive bezel turns counterclockwise with a resolution of a half-minute per click. The watch is water resistant to 300 meters/1000 feet.

My Seastar is the Seastar 1000 Powermatic 80 Silicium T120.407.11.041.01. This model has a beautiful midnight blue dial and matching timing bezel, the stainless steel bracelet, and the Silicium movement. I ordered mine from Amazon which is not an authorized dealer to save a few bucks, but also because this particular model doesn’t seem to be available from US dealers. It is listed on the international Tissot site but not the US site.

Silicium

About three years ago Tissot came out with an interesting movement upgrade – a silicon hairspring. They released it first in a special “chronometer” edition (“chronometer” meaning the COSC timekeeping certification of better than -4/+6 seconds/day rather than a navigational chronometer), and it has found its way into a few other of their watches.

About three years ago Tissot came out with an interesting movement upgrade – a silicon hairspring. They released it first in a special “chronometer” edition (“chronometer” meaning the COSC timekeeping certification of better than -4/+6 seconds/day rather than a navigational chronometer), and it has found its way into a few other of their watches.

Watch timekeeping accuracy is dominated by two factors – the rates of the balance wheel and hairspring. The balance wheel can affect timekeeping by changing size – if the balance wheel grows due to an increase in temperature, the watch will slow down. If the balance wheel shrinks due to a decrease in temperature, the watch will speed up. Similarly, the length of the hairspring affects the oscillation period of the balance wheel.

Watchmakers have spent a large amount of energy trying to manage this problem with bi-metallic compensating balance wheels replacing solid wheels and experimenting with metal alloys to reduce the dimensional change of components. Hamilton’s Elinvar hairspring material developed in the 1920’s was particularly impressive.

One other challenge was magnetism. If the hairspring becomes magnetized, the coils can stick to each other, drastically affecting the rate. Pocket watches made before 1920 are extremely susceptible to magnetic interference. Watches after that were somewhat better due to the reduced amount of iron in later hairspring alloys, but even modern watches can struggle with this.

Enter silicon. As silicon is non-metallic it is unaffected by magnetism. By the way, silicon and silicone are completely different things. Crystalline silicon is rigid and very hard. It is the basis for most computer chips. Silicone is the goopy stuff you smear around plumbing fixtures and windows and doors to prevent leaks. Watches use the former, not the latter. 🙂

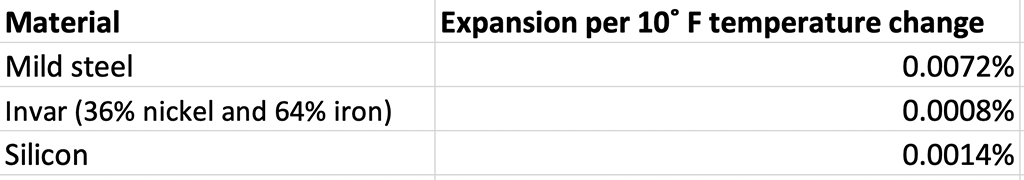

The above table is a comparison of the thermal expansion coefficients for various materials used in hairsprings: steel springs used in old watches, Invar 36 (representative of a number of similar low-expansion alloys) used at the end of the pocket watch era through the present, and silicon, which is just beginning to be used in watches. The thermal expansion coefficient describes how much the material expands or shrinks with changes in temperature.

For an uncompensated balance and all else equal, this means a watch with a mild steel hairspring would gain 600 seconds per day if the temperature rose 10 degrees. That’s obviously not great for a timepiece. Invar is almost 10 times better with an error of around 60 seconds per day rate change with a 10 degree temperature change. What’s interesting is that silicon is actually less thermally stable than invar is, with twice the movement over a given temperature range. If that’s the case, why is silicon so great? The key lies in what compensation can and can’t do.

Compensation

Compensation is the process of bringing something into balance: e.g. for every hour of your life you work, your job provides you with financial compensation. In a watch, we attempt to balance out any factors that might affect timekeeping. If something expands due to an increase in temperature, compensating for that must cause something to shrink to bring the watch back into balance.

Since about the 1870’s, the main method of timekeeping compensation in watches has been the bi-metallic balance wheel. A bi-metallic wheel is made up of two dissimilar metals laminated together that have different thermal expansion coefficients. The wheel has a split on each side, creating sort of an “S” shape. The material with the larger thermal expansion is on the outside of the wheel.

When temperature increases the hairspring lengthens which slows the watch; but this is compensated for by the outer brass part of the wheel with the higher thermal expansion coefficient. As the brass layer is bonded to the steel which has not expanded as much as the brass, the arms of the balance wheel bend inward which speeds up the balance wheel, compensating for the increase in length of the hairspring and expansion of the balance.

Bi-metallic wheels are very costly to make, and with modern materials available that have much better thermal stability such as glucydur and ARCAP, have fallen out of favor in modern watchmaking.

Practically speaking, anything that is predictable can be compensated for: temperature, humidity, various operating positions, etc. It is much harder to compensate for unpredictable things, such as magnetism, and this is where the magnetically impervious silicon comes in – there’s no need to compensate for something that has no effect.

How big of a deal is a completely anti-magnetic hairspring? I’m not entirely sure, but I will say that I have magnetized more than one pocket watch by carrying my iPad near the pocket with my pocket watch. My iPad keyboard cover has several strong magnets to attach the cover to the Ipad and also to keep the cover folded.

Fit and Finish

The Good

For a mid-priced watch I think the Seastar is well-done. The bracelet is comfortable and hasn’t pinched or pulled my arm hair. The timing bezel turns with a definite and satisfying click with no play in any direction, and being ceramic should stand up well to normal use; better than the aluminum bezel of sister company Hamilton’s Scuba. The dial is gorgeous and the lume is bright and easily lasts until morning.

The Bad

The crenelation on the timing bezel is pretty sharp. That makes it easy to grip, but occasionally in use I find that I rub my other hand on the bezel and it’s a bit scratchy. I also wish the bracelet clasp had a spring loaded latch rather than the friction latch that could wear over time. To be fair, I have a much more expensive watch with a similar system.

The biggest issue at least on my particular watch is that the timing bezel doesn’t line up perfectly with the 12 o’clock position on the dial. After looking at this more closely I think the issue is not the timing bezel as that lines up well with the bracelet, but that the movement is probably slightly askew in the case. The good news is this is probably fixable, but it is evidence of a hole in Tissot’s QA.

Performance

The mechanical Seastar versions use the Tissot Powermatic 80 movement, which is based on the ETA 2824-2 movement. The 2824-2 movement runs at 28,800 BPH. The Powermatic 80 movement runs at 21,600 BPH, which helps extend the runtime and reduce movement wear at the expense of a slight loss of smoothness of the second hand motion and maybe a bit of a hit to the ego having a slower-beating watch.

The first Tissot Silicium watch was the COSC-certified Ballade released in 2017. The Seastar doesn’t have a COSC-certified movement, but with high-tech watches, performance is often better than COSC-spec even if it hasn’t been officially certified. My Seastar runs at about -2 to -3 seconds/day, which is well within the COSC spec of -4/+6 seconds/day, and not far off of Rolex’s “Superlative Chronometer” rating of -2/+2 seconds/day. I haven’t owned the watch long enough to see how stable that rate is; I will try to remember to update this review after a few months of wear.

Update 11/22/2020 – After 3 1/2 months of wearing this watch most days since I’ve had it, I remain extremely impressed with it’s timekeeping ability. I’m currently running about -1 seconds per WEEK. Yes, I said per week, and not per day. I’m losing less than 1/8 second per day. This is quartz watch good. This is better than another brand’s “superlative chronometer” good. I’m amazed.

Conclusion

I really like this watch. My only complaint is the slight misalignment between the dial and the timing bezel. I bought mine from Amazon which is not an authorized dealer, so I don’t have the ability to complain to my dealer, and it’s on me to have it looked at by somebody if it bugs me too much.

A new watch is a bit like getting a new car; the excitement of something new can turn to obsession over the tiniest scratch or mark. I bought this watch to be a regular wearer – something a little nicer than some of my beater watches, but not so nice that I would be afraid to wear it. I think the Seastar fits the bill nicely. It’s every bit as functional as an expensive top-tier dive watch without the deep bank account hit and the homeowner’s insurance jewelry rider.

6 replies on “Tissot Seastar 1000 Silicium Review”

Lovely review- thank you. I purchased this watch after looking at MANY alternatives. Quite pleased with it. Considering the movement, it is an enormous bargain.

I’m glad you agree. The timekeeping of the watch is insanely good – far better than my much more expensive big-name Swiss watch. I set mine on November 1st due to the time change and 3 weeks later I’m 3 seconds slow. This is extremely impressive.

Super recenzija, međutim što se preciznosti sata tiče, moj Tissot silicium dnevno premašuje +15sec dnevno. Sat je prekrasan, ali sam potpuno razočaran preciznošću.

English translation:

Great review, however as far as watch accuracy is concerned, my Tissot silicon daily exceeds +15sec per day. The watch is beautiful, but I am completely disappointed with the accuracy.

I also loved your review. Also the lessons about watch manufacturing and materials will help on my friends meetings. I bought this watch also I am very pleased with it accuracy less than 5 sec/day. You know I can`t find the specifications on this watch on Tissot home page. Again, thanks a lot.

Great review and what a lesson about watches. My Tissot is now -2 Sec/day and I can’t add or remove a word of your excellent review. Thanks a lot for this review.